Diamonds are Forever

Whether sitting pretty atop a ring, dangling from a pendant earring, or encrusted into a designer watch, a twinkling diamond commands attention. Certainly, everyone knows that nothing but a diamond ring will do when pledging eternal love to your sweetheart. So, how did our romance with this precious stone begin?

Remarkably, diamonds are a form of carbon, one of the most abundant substances on the planet. It takes about a billion years of intense heat and pressure deep below the earth’s crust for a lump of graphite – carbon’s most common form, best known as the “lead” in pencils – to form into the world’s hardest natural substance. In fact, the only thing that can scratch a diamond is another diamond, which is why it is so sought-after as an industrial abrasive.

The clear, octahedral crystal was first discovered at least 3,000 years ago in India

The clear, octahedral (double pyramid-shaped) crystal was first discovered at least 3,000 years ago in India, where its unique beauty and imperviousness made it revered as a talisman against evil and harm. Interestingly, although its mines were exhausted long ago, India has stayed the world leader in diamond cutting and polishing, handling over 90 percent of rough stones.

Diamonds as a symbol of romantic devotion go back to the European nobility of the Middle Ages, when they were left in their natural form and valued less for their beauty than as uncommonly potent love charms. Legend had it that Cupid’s arrows were tipped with the super-tough mineral because it could pierce even the hardest heart – its name in English comes from the Greek adàmas, which means “unbreakable.”

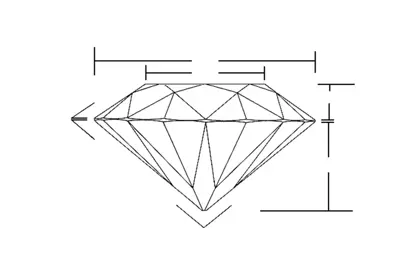

Over time, jewelers realized that pre-cise cutting, or faceting, was required to ful–ly capitalize on the diamond’s amaz-ing optical qualities. Indeed, it is considered the most important of the four “Cs” used to rate a diamond’s quality, the others being carat weight, equal to 200 milligrams; color, ranging from colorless to light yellow (for white diamonds); and clarity, which varies from flawless to “included,” or blemished. Together, these determine the fifth “C,” cost.

Faceting is what produces a diamond’s “fire,” (the refraction of light into its component colors), its brilliance (the reflection of light back to the eye of the viewer), and its scintillation (the sparkling effect when a diamond is turned in the light). Gem cutters slowly developed increasing-ly complex arrays of facets, culminating in 1919 with the 58-facet round brilliant cut, created by Belgian-born Marcel Tolkowsky who designed a set of “ideal” diamond proportions according to mathematical principles. Other “ideal” round brilliant cuts that factor in optical properties have been designed since then, but Tolkowsky’s remains the benchmark. The familiar pentagon-like profile is the most popular cut, accounting for over 80 percent of all finished diamonds.

The most popular fancy cut is the princess

Unlike fancy cuts, there are standardized grades for the round brilliant cut among all the major diamond certification bodies: the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), Hoge Raad voor Diamant (HRD), and American Gem Society (AGS). Gem cutters also like the shape because it allows them to cut two diamonds – one big and one small – out of a single, regularly shaped rough stone.

The most popular fancy cut is the princess, a square or slightly rectangular shape that can feature as many as 144 fa-cets. Since diamonds naturally have four corners, this cut preserves about 80 percent of the original rough. As a result, princess-cut diamonds are less expensive than round brilliant-cut diamonds of the same carat weight. In 2005, the AGS launched a stan-dardized system for grading princess-cut diamonds, the first and only one of its kind.

There are countless other fancy cuts, many of them proprietary, such as Bez Ambar’s modified princess Quadrillion, Christopher Designs’ modified round brilliant Crisscut, or Trillion Diamond Co.’s triangular Trielle. Most of these are brilliant-cut diamonds, which emphasize a diamond’s reflective properties (and can better hide inclusions), while step-cut diamonds (think of an emerald) emphasize a diamond’s clarity and color. The Asscher cut, a square with cut-off corners, is a step cut first popularized in the Art Deco era and is making a comeback.

There are slender shapes, such as the marquise (football) and baguette (rec–tangular) cuts, as well as round shapes like the cushion (oval) and pear (teardrop). The choices are endless, which is why a good jeweler is indispensable. They will offer suggestions about the many different pieces or loose diamonds, narrowing the choice down to what best suits the occasion and the customer. In the end, beauty is in the eye of the be-holder, but if a diamond catches your eye, you’ve found a partner for life. After all, diamonds are forever.